In Search of Home, I Found Myself

Dedicated to the past I carry in my body, and to the hands that hold me here, now.

Octopuses in captivity never stop looking for a way back home, slipping through cracks, crossing floors, always searching for the sea.

People believe taking them from the ocean will mean a better life, but the octopus knows otherwise.

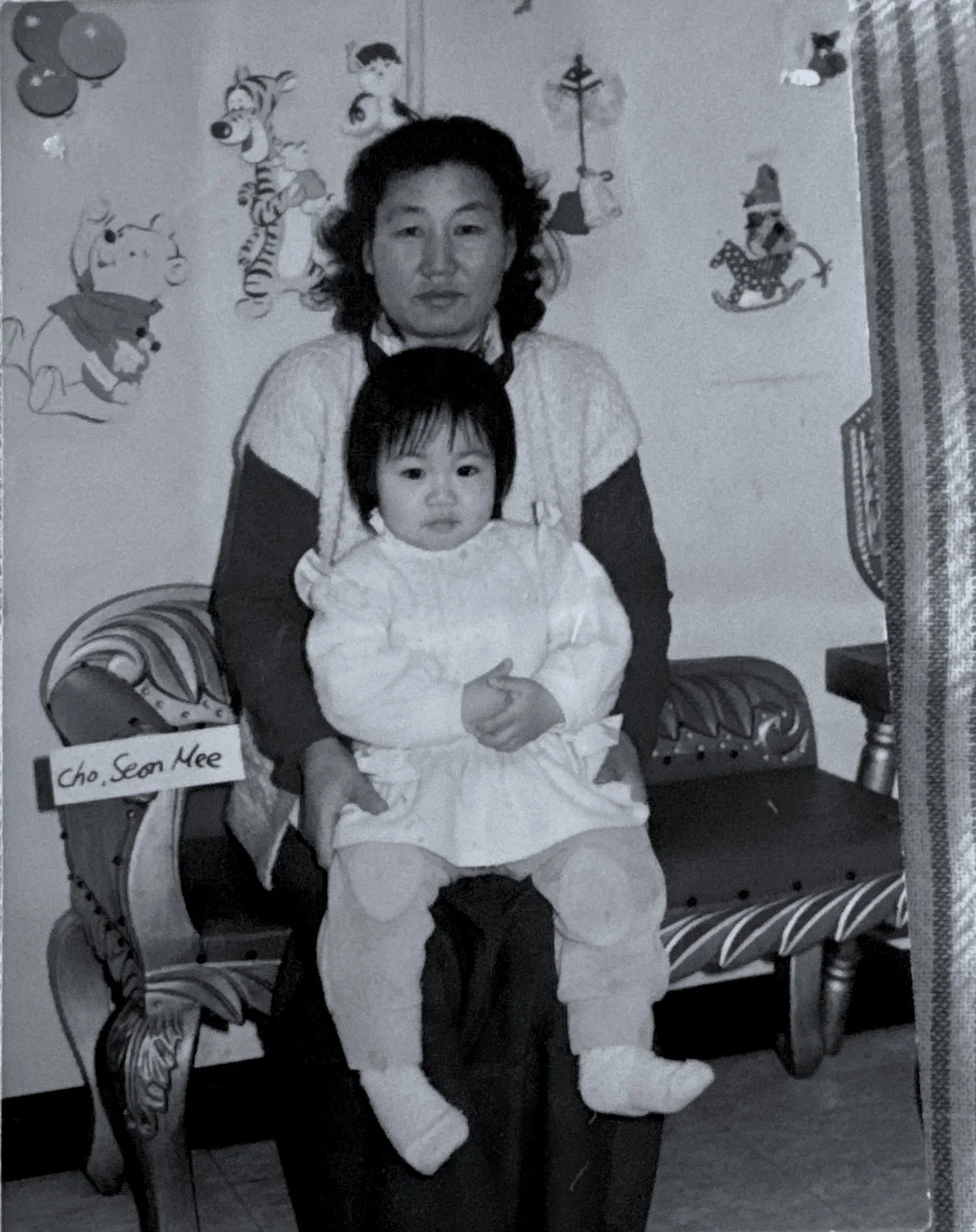

I was lifted from the waters of South Korea and flown across an ocean when I was two and a half years old. Too young to remember, but old enough for my body to hold the memory.

Adoption was supposed to mean the same for me, safety. A better opportunity. A family to love me. In truth, it was the beginning of a lifelong search for belonging: to my family, to my culture, and most of all, to myself.

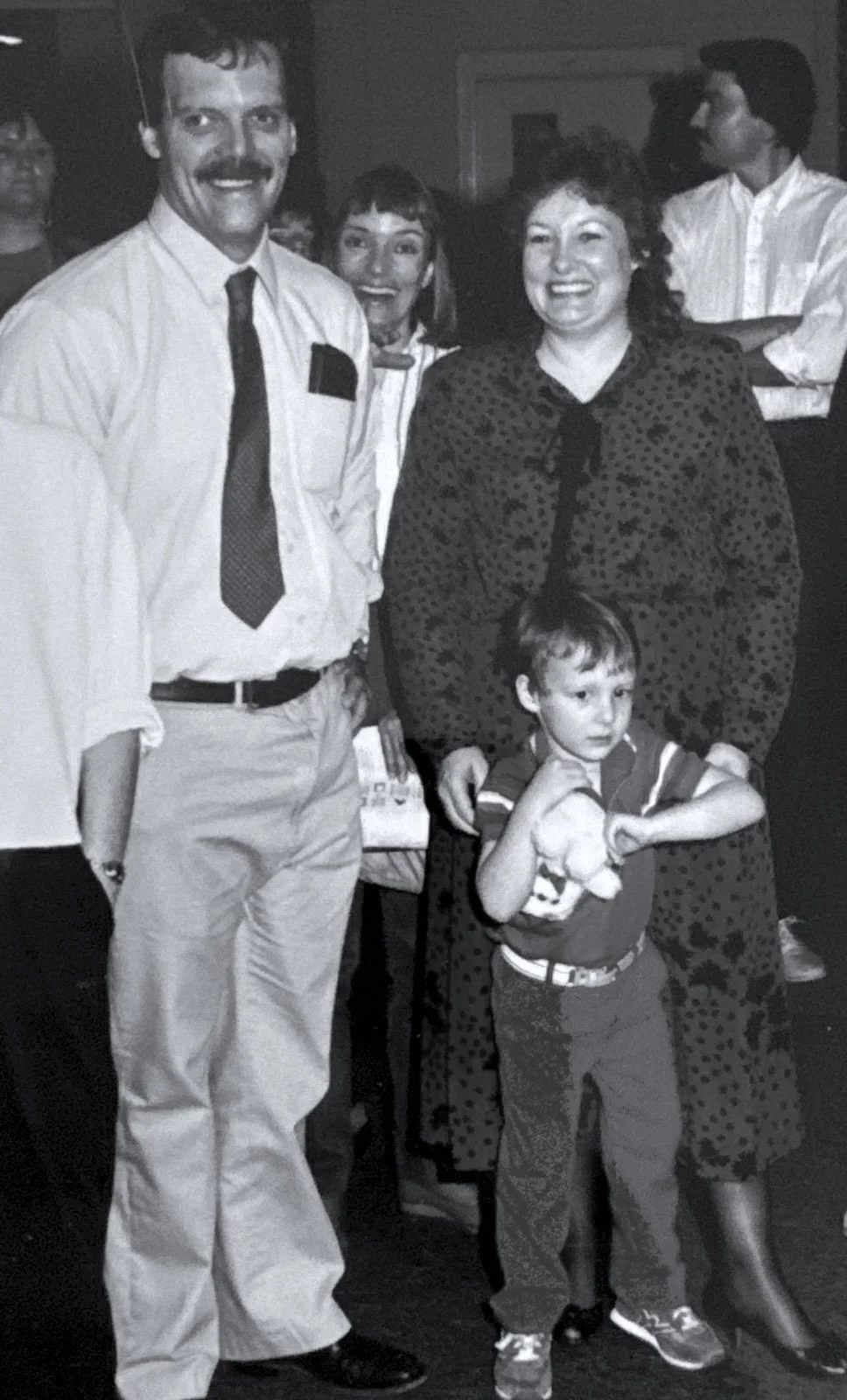

My new family: my mother, my father, my brother, came from a long line of ranchers, people who lived close to the earth and measured time by seasons, not clocks. I was raised in that rhythm.

I learned to get my hands dirty, to fix what was broken, to work hard and stay quiet, to have faith in God and lend a hand to those with less. Sundays were for church. Weekdays for labor.

I grew up volunteering beside my mom at the local shelter, serving food to strangers, scanning the line for someone familiar, a nose, an eye shape, a smile that might look like mine.

My grandmother, my mom’s mom, was one of my first safe harbors, her love steady, uncomplicated.

My father’s mother, however, never accepted me. I was not her grandchild. From her, I learned that love could be conditional, a lesson I would spend years unlearning.

An octopus survives by shifting its colors and shapes to fit its surroundings. And like the octopus, I learned early to adapt. To blend in, to stay safe.

I softened my edges, muted my questions, and reshaped myself to fit. But beneath it all was a quiet ache, a longing for something I couldn’t name.

Adoption wasn’t the only thing I carried quietly as a child. I was also navigating my queerness long before I had language for it. I didn’t know if I’d be accepted for who I was. Not just as a Korean adoptee in a white family, but as someone who would one day transition. I kept that part of myself buried deep, afraid that the truth would make me even harder to love.

Octopuses can change their entire appearance in a flash; skin, color, even texture. But underneath the disguise, they remain the same being. For me, transition was the opposite: the shedding of disguise, the revelation of what had always been true.

Starting my transition was the best decision I have ever made. It was a step toward wholeness, toward aligning who I am inside with how the world sees me. But even as I found peace in my gender, I couldn’t ignore the part of my story I’d left untouched, my adoption.Octopuses are the only species that can regenerate a fully functioning nervous system, rebuilding the very pathways that help them feel and move through the world. And in 2019, I realized my own nervous system had frayed, that the limbs I once trusted were gone.

Like the octopus, I began the slow work of regeneration; relearning what it meant for my body to feel safe, to belong, to trust what was real.

I stopped running and found other adoptees who understood the ache I’d carried for so long — a community that helped me heal and reminded me I didn’t need to carry this burden alone.

I am often asked if I want to find my birth parents. The answer is complicated. Yes, I long to see myself in someone else.

But I have also learned to forgive.

I forgive my birth mother, for what she did or didn’t do before I was adopted, for what was and wasn’t in her control.

I forgive my adoptive parents, for not knowing what was coming when they brought me home, for not knowing how to raise a child of color in a world that insisted on being “colorblind.”

And I forgive my brother, someone I don’t currently have a relationship with, who has yet to understand the depth of pain adoption can carry. Even so, I love him.

There was a time I didn’t think I’d live past thirty, a time when the weight of grief and unanswered questions felt impossible to bear. I later learned what my body already knew; that intercountry adoptees are 3.6 times more likely to die by suicide, and trans folks face that weight more than fourteen-fold.

But today, I am here.

Grateful for survival, for healing, for the constellation of people who held me when I thought I might fall apart.

In the end, I am stitched together by all of them. The ones I wonder about, the ones who raised me, the ones who stepped up, and the ones I chose.

They are the arms of my octopus, the many ways love has reached for me, pulled me back, and carried me forward.

I am letting go of what I cannot carry. I am finding peace in the wreckage, and like the octopus, regenerating what was lost.

And for the first time, I feel like I am living. Fully in my body, fully myself, and finally home.